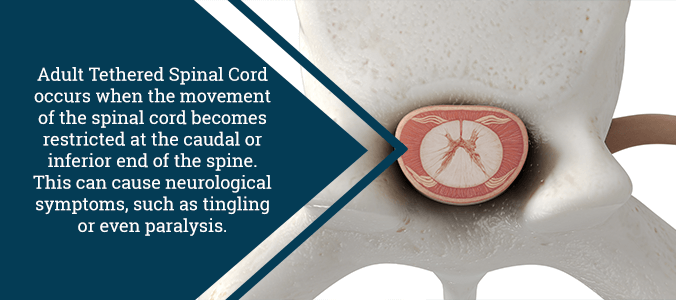

What is Tethered Spinal Cord?

Tethered cord is a blanket term that doctors apply to a variety of different conditions. The common thread between tethered cord conditions is that the spinal cord’s movement is limited at its base. Because of this limitation, the spinal cord cannot move up and down inside the spinal canal during daily activities. Instead, the cord pulls against the restriction. In milder cases, this pull on the spinal cord is minimal and typically does not lead to damage. That being said, patients with more severe cases may exhibit the symptoms of a spinal cord injury, such as lower body paralysis or a loss of sensation.

Tethered cord may be present at birth (congenital), or it may arise later in life (acquired). In congenital tethering, doctors typically find the condition during childhood, although this is not always the case. Sometimes, tethering is not diagnosed correctly or discovered until adulthood. In adults, a diagnosis of acquired or congenital tethered cord is relatively rare.

Symptoms of Tethered Spinal Cord

In adults, symptoms of tethered cord usually develop slowly. However, if left untreated, these symptoms may become quite severe. Common symptoms include back pain that radiates to the legs, hips, and rectal or genital areas. Many also report feelings of weakness or numbness in the legs, as well as muscle loss. In some cases, bladder or bowel dysfunction may be present.

Back pain associated with tethered cord is often exacerbated by a variety of common bodily positions. This includes bending slightly forward or sitting upright with crossed legs. Additionally, carrying a moderate weight, such as a stack of books, at waist level can also aggravate this condition. This pain pattern is commonly referred to as the “3-B sign.” This stands for Buddha-sitting, baby-holding, and bending.

Additional symptoms for tethered cord may include:

- Lesions on the lower back

- Discoloration of the skin in the lumbar region

- Trouble walking

- Muscle contractions

- Tender spine

- Lumbar scoliosis (a sideways curvature in the lower back)

- Hairy patches of skin in the lumbar region

- Deep dimples in the lumbar region

- Fatty tumors in the lumbar region

It is relatively rare for this condition to remain undetected after a child has grown. However, in such cases, the pressure on the spine is greatly worsened. This leads to increasingly severe sensory and motor problems.

Causes of Tethered Spinal Cord

Normally, the bottom tip of the spinal cord sits across from the disc between the first and second vertebrae in the lower back. In people with myelomeningocele (spina bifida), the spinal cord does not unbind from the skin properly. This causes abnormalities in the spine’s structure, and as a result it becomes tethered.

Patients with lipomyelomeningocele have a fatty mass on the end of their spine. The fat on the tip may bind to the fat above the thecal sac (the fluid-filled sac in which the spinal cord floats). Essentially, the spinal cord becomes stuck (tethered) to this fatty mass in the back.

In many patients, a thickened filum terminale often leads to the condition. This structure is a fragile strand of fibrous tissue that connects the end of the spinal cord and the sacrum. Normally, this part of the spine is very flexible, which allows the spinal cord to move. If the filum terminale thickens it becomes inelastic and causes the condition. This cause of tethered cord is more commonly found in children than it is in fully grown adults.

Additionally, there are other potential causes of the condition:

- Failed back surgery syndrome

- A history of spine injuries, such as spinal fractures

- Dermal sinus tract (a rare condition that causes abnormal connections between the skin and spinal cord)

- Lipoma (a small growth of fat)

- Spinal cord infection

- Infection or development of scar tissue

- Diastematomyelia (a rare congenital anomaly that causes the spinal cord to split)

Affected Demographics

Tethered spinal cord syndrome affects both males and females equally. Keep in mind, however, that these figures are not exact when extrapolating to the general population.

Previously, the diagnosis of tethered cord syndrome has been controversial. Even today, the disorder often still remains unrecognized and undiagnosed. Thankfully, tethered cord syndrome is now considered a clinical entity of importance. To aid with this, a definition for true tethered cord syndrome now exists. The definition limits the disorder to patients who exhibit neurological signs and symptoms due to inelastic structures that anchor the caudal end of the spinal cord. As a natural cause of these limitations, there are cases in which patients have similar signs and symptoms of true tethered cord syndrome, but actually have a different problem altogether. Most of these examples involve associated defects that cause compression, impaired blood flow of the spinal cord, or failure of neuronal development. Generally, patients with these anomalies suffer from complete or nearly complete paralysis in the extremities. Additionally, they also suffer from total loss of rectal and bladder control.

Similar Disorders

Comparisons to related disorders may be useful to establish a differential diagnosis. Symptoms of the following disorders may present signs and symptoms similar to those of tethered cord syndrome:

- Extradural lesions

- Intradural-extramedullary lesions

- Intramedullary lesions

- Extraspinal lesions

- Myelopathy

- Peripheral neuropathy

Children with spina bifida show a wide variety of symptoms and physical findings. This, however, depends on the severity of the defect. Anomalies connected to the caudal end of the spinal cord can be surgically repaired with an excellent outcome. That said, untethering surgery will have no neurological benefit for those who suffer from complete paraplegia.

Diagnosis of Tethered Spinal Cord

A performing doctor may use the following tests to confirm a diagnosis:

- Myelogram: Combination of x-ray imaging and use of contrast material on the thecal sac. This can reveal any compression to spinal nerves.

- MRI: This device uses strong magnets and computer imaging to create displays of the body’s anatomy. This can show any areas that a tethered spinal cord would affect. Additionally, it will show any enlargement, degeneration, or displacement.

- CT Scan: Another form of diagnostic imaging that utilizes x-rays. Physcians often use this as a supplemental test to a myelogram. Naturally, this is because it shows the movement of the contrast material through spinal structures.

- Ultrasound: The doctor puts a water-soluble gel on the skin and then places a transducer on the gelled area. The gel helps to transmit the sound to the skin’s surface. The doctor then turns the ultrasound on to obtain images of the spinal cord and the thecal sac.

Surgery for Tethered Spinal Cord

Your doctor will only perform corrective untethering surgery if your condition gets progressively worse over time. Surgery involves opening the scar from the prior procedure down to the covering (dura) over the affected area. In some cases, your surgeon will remove small portions of the laminae to relieve pressure and provide better access to the spine. The covering is then surgically accessed and the spinal cord and myelomeningocele are moved aside from the scarred attachments to the surrounding area. Once your doctor frees the myelomeningocele from its scarred attachments, he or she will reseal the dura and wound, thus completing the procedure.

The patient can typically resume everyday activities within a few weeks or so. Recovery of lost muscle and bladder function varies on a case-by-case basis. Generally, the complication rate of this procedure is usually only 1 to 2 percent. Complications may include bleeding, infection, damage to the spinal cord or myelomeningocele, decreased muscle strength, and bladder/bowel dysfunction. Most patients only require one untethering procedure, but some cases require multiple procedures.

In addition, if your tethered spinal cord has resulted in scoliosis pain, you may need to undergo additional procedures. Your doctor will decide which course of action (from spinal bracing to anterior lumbar interbody fusion) is right for you.

If you have a debilitating spinal condition that needs treatment, please contact us at (855) 220-6966. Dr. Jason E. Lowenstein specializes in adult and pediatric spinal deformities, as well as in rare conditions that cause scoliosis. Under Dr. Lowenstein’s care, you can rest assured that you will receive a personalized care plan specifically designed to treat your needs.